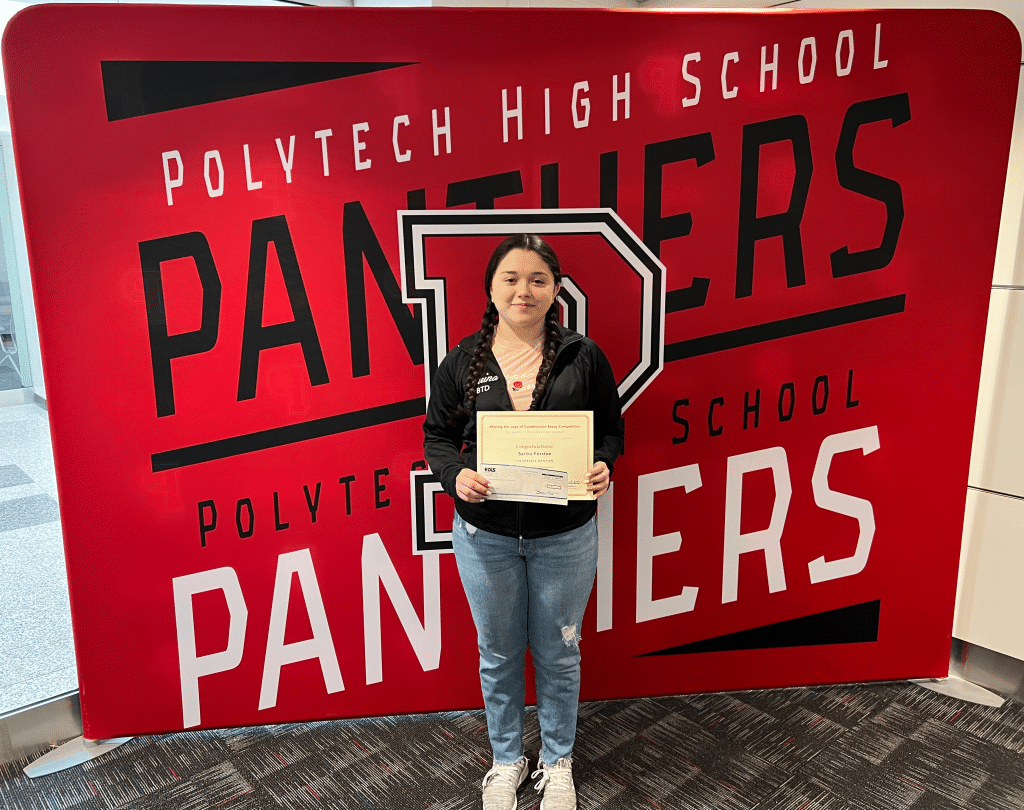

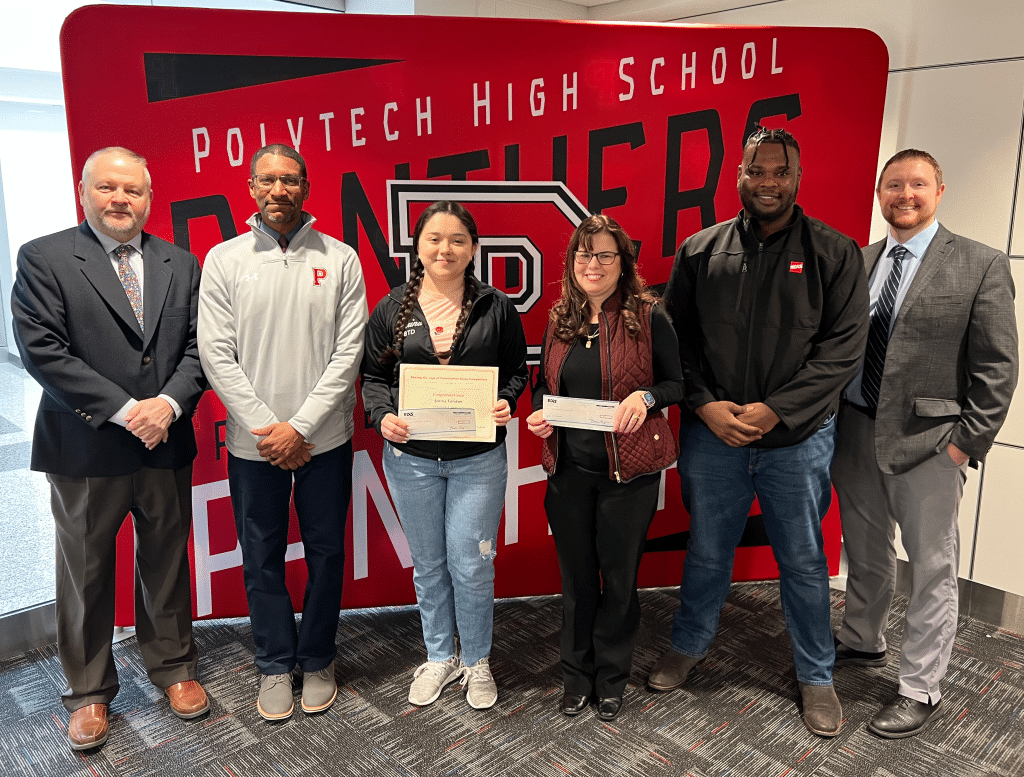

The Sharing the Joys of Construction Essay Competition was created by EDiS Company in 2021 for Delaware trade and vocational high school students to shine a spotlight on the positive impact diversity has in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry during Black History Month. Students wrote about individuals or companies who have inspired them or have had a positive impact on the built environment. First place junior Nasir Williams, second place freshman India Motley, and third place junior Gabrielle Smith won $750, $500, and $250 respectively. Sussex Technical High School runner up is senior Tyler Keyek, winning $100, and the POLYTECH High School runner up is Sarina Forston, winning $100. Each winner had their owner sponsor teacher who won $100 to use in their classrooms.

Grade: 9 School: POLYTECH High School

Sponsor Teacher: Mrs. Danielle Mello

Ethel Furman

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Rosa Parks. Malcom X. Thurgood Marshall. John F. Kennedy. All those names come to mind when anyone thinks of Civil Rights Activists-people who fought and paved the way for African American rights in America. However, there are many other people that were involved in this movement that are either forgotten about or not known as well. One of them is an African American architect. Ethel Furman was an influential African American and female architect in the industry that contributed greatly to the construction environment throughout her whole existence. Throughout her early life, personal life, working in the industry, and her legacy left behind, she impacted this industry.

Early Life

Furman’s connection with the industry started when she was young. She was the daughter of a Richmond Building Contractor (Library of Virginia, 2023). Because she was raised by a contractor, she was exposed to this environment very early on in her life. Her dad was a contractor because there were many barriers to becoming a licensed architect, so African Americans instead became “contractors” (Richards, 2021). As a child, she went to work with her father, Madison Bailey, where she learned to build and utilize the raw materials. She also picked up the trade’s language when tagging along at job sites. This experience helped her understand more what was going on. For education, “She attended Armstrong High School until the family moved to suburban Philadelphia, where she graduated from Germantown High in 1910” (Kollatz Jr., 2018). Around 1915, she was privately tutored, and she apprenticed in New York. While apprenticing in New York, her knowledge was furthered from what she already knew from her father. She returned to Virginia to further her career in 1921 (Richards, 2021). The knowledge that she learned during her childhood with her father and her private tutoring/apprenticeship in New York would help her advance her career later in her life.

Personal Life

Furman’s personal life also provided many challenges to her construction career. She married William H. Carter in 1912, two years after she graduated from high school. They had two kids together – Thelma Carter Henderson and Madison before their divorce in 1918. Later on, she married Joseph D. Furman and named their son J. Livingston, which was during the time period that she apprenticed in New York City (Kollatz Jr., 2018). While working for her father after returning from private training in New York, she also raised three children and worked many other jobs in order to make enough money to support her family (Library of Virginia, 2023). This work ethic exemplifies how hard she had to work.

Not only did the construction industry take a toll on her physical abilities, but she also had to have a higher mental capacity to take care of three children and work other jobs on top of this. She was an active member of her church in addition to participating in the Heart Fund, the March of Dimes, and voter registration drives (Kollatz Jr., 2018). By her participation in these movements, she showed her commitment to volunteering. Despite having three children to take care of, Furman remained dedicated to her work and played an immense role in her community, which helped her with her profession.

Working in the Industry

Furman’s demanding work at her job continued when she returned from New York. Furman’s goal was to provide clients with homes that were built from quality materials but were also affordable and aesthetically pleasing (Kollatz Jr., 2018). A photograph from the 1928 Negro Contractors’ Conference held at Hampton University showed she was the only woman in attendance. She was one of the firsts in her field. Her social ties in her community also greatly

helped her career. One of the connections she had was to Maggie Walker, the first African American in the United States as a president of a bank, St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. Historians do not know the exact relationship between the two, but they believe that it was beneficial for them both. Walker was an advocate for African Americans and women, which likely could have been Furman (Richards, 2021).

These connections were important, especially with her being the first in her area. Furman also showed her business savviness in getting her drawings approved by others. Furman would often submit her work through coworkers that were male because she was discriminated against (Richards, 2021). By having them submit them, they were more likely to be used, which showed how she found a way to overcome the adversity of the time.

She also went on to further her career, which influenced the industry. Around 1944-1946, Furman earned her certificate in architecture at the Chicago Technical College (Richards, 2021). During the time that Furman worked, she designed around 200 buildings. Some of the buildings she designed were Fair Oak Baptist Church in Richmond, St. James Baptist Church in Goochland County west of Richmond, and Mount Nebo Baptist Church in New Kent County. She also was responsible for an addition to Richmond’s Greek Revival Fourth Baptist Church. Furthermore, she designed the childhood home of the first African American to serve as a governor in the U.S. post reconstruction, Douglas Wilder. She is responsible, along with Charles Thaddeus Russell, for developing Church Hill, which was a thriving African American neighborhood in the South (Richards, 2021). She also won an award for her work. In 1954, she earned the Walter Manning Citizenship Award (Richards, 2021). However, “Unfortunately, in her declining later years and during a move from the Q Street house, the bulk of her early plans, client correspondence and business materials was lost” (Kollatz Jr., 2018). This move was devastating because many of her works had been lost. Furman worked hard in the construction industry but passed away in 1976 (Library of Virginia, 2023). Her work was also posthumously honored, because of the importance her impact had.

Legacy Left Behind

Furman’s work and accomplishments left a lasting impact on her community. Because she faced racism and sexism, many books about the history of architecture in Virginia do not include her name despite her being the first, black female architect in the Commonwealth of Virginia (Richards, 2021). However, she has been recognized by people for her achievements. “Some traces of Furman’s life and career have been celebrated through digital exhibitions and retrospectives by the Library of Virginia, Virginia Humanities, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and Docomomo” (Richards, 2021).

Additionally, the Library of Virginia has preserved around two dozen of Furman’s drawings in addition to evidence of business transactions and photographs (Richards, 2021). A street in Church Hill was named after her, (Richards, 2021), and “Her 1962 design for the educational wing of Richmond’s Fourth Baptist Church was recognized on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Church Hill North Historic District extension in 2000” (Library of Virginia, 2023). Furman was an honoree in 2010 by the Library of Virginia for Virginia Women in History (Library of Virginia, 2023). The awards and recognition may have been long overdue, but the work Furman completed cannot be argued.

Conclusion

Furman’s perseverance and ethics led her to become an entrepreneur in her time, fighting both gender and race barriers. She accomplished many things throughout her life in the construction field, even from when she was young since it played such a huge role in her upbringing. Regardless of anyone’s race, gender, or any other differences, they can achieve their goals when they put their mind to it. Furman was the epitome of that when she broke the barriers in the construction field. Ethel Furman left behind so much in this industry, and her legacy can never be forgotten.