Integrity seems to be one of those words that ends up on every company’s “values” list. Integrity is printed on company brochures, annual reports, and featured in displays around offices across the country. Sadly, it is getting watered down to the point where we forget its meaning.

Recently, I learned that I had provided a prospective client with erroneous information. I had made a miscalculation and to admit such a mistake would not only be embarrassing, but might result in the loss of a potential project that we had spent a great deal of time and effort trying to obtain. So, I thought through my options. I could wait, and after the project was awarded and the contract negotiations were in full swing, I could have just passed the “error” along with the hope that it would slip by. But I knew what I had to do. I came clean, praying for the best.

During my moments of deliberation (and a few hours of lost sleep), I remembered an article that I had read many years before in New Yorker magazine about the mistake and subsequent action taken by a renowned structural engineer, William LeMessurier (pronounced LeMeasure). I looked for the article but couldn’t find it. I mentioned it to Andy DiSabatino who instantly put his hands on a copy. To Andy’s credit, he keeps a copy close at hand and has referred to it numerous times.

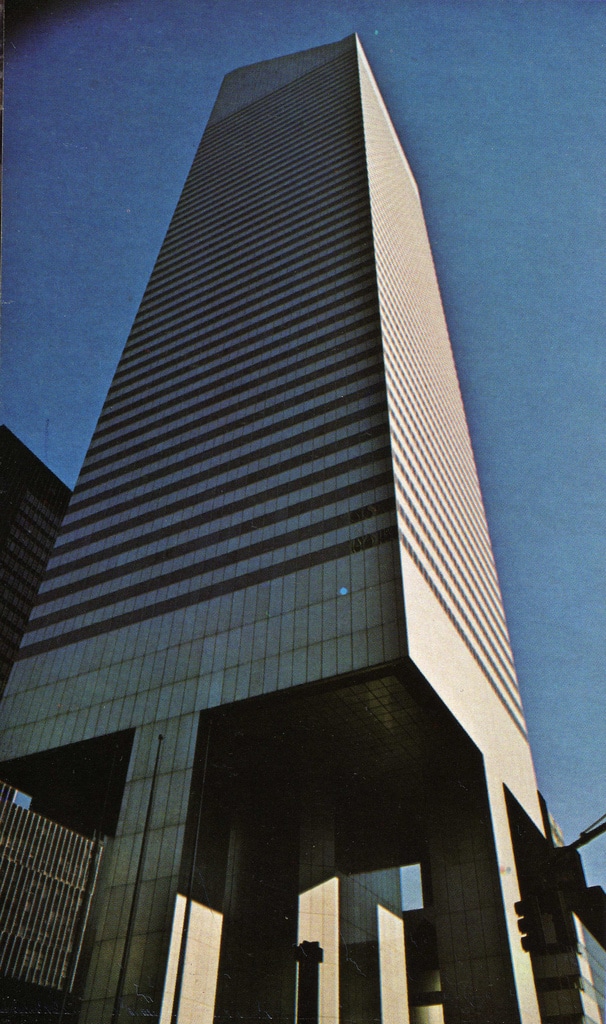

Anyway, Mr. LeMessurier designed the structural steel framing for the 59-story Citicorp Center which was constructed in the 1970s in Manhattan. After receiving a telephone call from an engineering student who was studying the structural framing of the building and who subsequently questioned the structural design, LeMessurier determined that he had made a potentially catastrophic design error.

Anyway, Mr. LeMessurier designed the structural steel framing for the 59-story Citicorp Center which was constructed in the 1970s in Manhattan. After receiving a telephone call from an engineering student who was studying the structural framing of the building and who subsequently questioned the structural design, LeMessurier determined that he had made a potentially catastrophic design error.

So, a year after the building had been occupied, it was found to be structurally deficient in a strong wind event. To make matters worse, this discovery occurred during the summer of 1978 with the hurricane season fast approaching. Over 200 bolted chevron bracing connections throughout the fully finished footprint of the building needed to be reinforced with two inch thick plate. So, beginning at 5 pm each evening and completing work at 5 am the next morning, construction teams had to demolish drywall and ceiling tile, build plywood enclosures, and proceed to weld the steel connections. In addition, before the bankers’ workday started, all of the debris had to be cleaned up as if they had not been working overnight. This carefully coordinated work occurred every night for over a month. With careful coordination and the herculean effort of many involved, the structural framing was made sound.

William LeMessurier was quoted saying, “You have a social obligation. In return for getting a license and being regarded with respect, you’re supposed to be self-sacrificing and look beyond the interests of yourself and your client to society as a whole. And the most wonderful part of my story is that when I did it, nothing bad happened.”

Fast forward to the summer of 2011 in Wilmington, where my problem was not nearly as perilous as LeMessurier’s. I confessed my error. Fortunately for me, my prospective client was totally understanding of my mistake (which cost his firm more money) and awarded us the project. Thankfully, “the most wonderful part of my story” as in LeMessurier’s, “is that when I did it, nothing bad happened.”